Wednesday, June 30, 2010

The Trial

She tried to forget him. He tried to forget that she was trying. She tried exercising more. He tried drinking less. She tried her friends' patience talking about trying to forget. He tried not talking to his friend about her. His friend tried not to listen while thinking about her in different contexts. First one, then another. She tried adjusting her routine: her path to work, her lunch order, the treadmill at the gym next to the treadmill where his friend works out. He tried not to become alarmed at the thickening texture of his trying. His friend tried to avoid his phone calls. She tried not to feel guilty. He tried to get used to hanging up the phone before voice mail came on. He tried to get used to evenings. He tried not to feel ashamed when he saw his friend holding her hand on the street. They tried not to see him staring. He tried on a pathos. She tried on a remorse. His friend didn't have to try, for he was always successful at anything he did.

Monday, June 28, 2010

From a Notebook (July 2009)

Thought versus the senses. Religion reconciled them, or rather put the senses in service to a prescribed thought. Philosophy versus aesthetics and poetry. Philosophers are perpetually on guard against the seductions of poetry, against metaphor, against taking the world of the senses for the only ground, which obscures truth. Poets are not so guarded but trespass exuberantly, willing to turn any turn of thought or discourse--any language, even and especially philosophical language --into a trope. to aim at truth must poetry then be tropeless--that is, not poetry? It must obey its own law. Yet I'm tantalized by the possibility of a tropeless imagination. Badiou calls it mathematics.

Digression on a (male) fantasy of writing: Betty Blue. In which the animalistic young hero Zorg drives a big machine and has wildly sublime sex with a beautiful young woman while filling an endless series of black notebooks with--what? The muse Betty finds them, types them up, finds a book in them--a novel. And all Zorg has to do to enjoy his success thereafter is smother poor mad one-eyed Betty with a pillow.

The dream there is that writing shall be indistinguishable from life, a life lived abandoned from responsibility to anything but the moment, the sensation. Erotics of the pen, its motion. The labor, the editorial intervention, is given over to a female other, and it drives her mad.

Energy and melancholy. Energy of melancholy. Melancholy as economy: the four humors are systems, an apparatus, for the management of human energy. Melancholy concentrates--the sanguine transmits--the phlegmatic stores up--the choleric broadcasts and scatters. Lisa Robertson: "the little drama of sensitive /expenditure."

Put the question differently. Can poetry be laicized? The fundamental religious impulse is to turn life into allegory: reality is displaced in the name of the divine, the ineffable, the unperceived. Poetry can try and return our attention to matter--to things--yet these things take up numinosity simply by being indicated, as a boat takes on water. But why should poetry be different from other structures of thought and feeling? All the modern languages claim to discover the operations of the not-directly-perceivable. Marx: capital. Freud: the unconscious. Darwin and evolutionary biology: the selfish gene. Badiou suggests that poetry creates a space for choice between and among imperceivables--that is, it creates subjects--through subtraction (Beckett) or multiplication (Pessoa). It's the angle of engagement that matters.

Not then a poetry (or a fiction) that excludes mimesis but which tests it through estrangement (ostranenie), through deliberately "unnatural" (what follows) arrangement, narrative, syntax. Syntax is where the action is--in existential terms, it's where decision happens. The syntax of the novel is called plot. The novel tests representation without abandoning it, though less rigorously perhaps than an Oulipian constraint or procedure would. Ideally I produce something--call it "decisionality"--for the reader without subtracting every readerly pleasure.

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

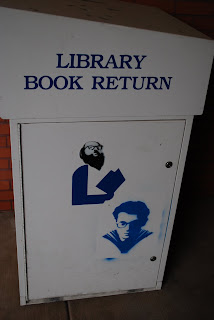

Book Return: Notes from Naropa

Outside the Allen Ginsberg Library at Naropa University.

For one solid week I took leave from my family and from my identity as poet to be a student in Laird Hunt's fiction workshop at Naropa University's Summer Writing Program. I arrived on Sunday afternoon filled with a mixture of excitement and nigh-existential nausea, such as I imagine afflicts secret agents. What would it be like to begin at the beginning--to sit at the seminar table and not be running the seminar--to be an unknown quantity in a tight-knit and storied community--to have so many poetry friends and acquaintances on the faculty while I went as a paying customer?

View of Naropa's front lawn, with a rather splendid tree.

Reader, it was glorious. Having checked my ego at the door, it was delightful to meet my fellow students around the ultramodern, coffin-like table in the shiny new Administration Building, and simply be one of them. I was happy to not be the oldest student in the class; there were quite a few twenty-year olds (a talented, ambitious, articulate lot, I hasten to add--like the best of my own students) but I was not the only one in his thirties and a couple of folks were in their forties. And looking around the room, especially once the class got going, I realized the benefits of taking a creative writing class as a full-fledged adult. I was not there to discover who I was, but what I was capable of doing. There was no vertigo, no posturing--I'm glad to say there was very little of this from my classmates, either. We got right down to business.

The workshop was excellent, not least for its being a workshop in a truer sense than usual: the emphasis was not on critique, but on producing new work. We read bits of the things we were writing, but the point was not to correct or polish this writing (or to grandstand opinions about it) but simply to hear it--to have a sense of the others were writing, and the immensely varied ways in which we were responding to the prompts and assignments. The title of the course was "Histories"; here's the description as it appears in the catalog:

Historical figures like Herodotus, Hannibal, Jesus of Nazareth, and Calamity Jane have all served as energy nodes around which writers have built significant works of prose. We’ll examine texts like Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter, Selah Saterstrom’s The Pink Institution, and W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn to explore that prose which, if we can kick awake that poor overworked pearl, posits the historical as its grain of sand. Students will produce their own writings for consideration and helpful critique.

I had had a sense, from his fiction and the little I knew of his biography, that Laird Hunt would be the ideal teacher for a poet trying his hand at fiction, and the gamble paid off. He spends a lot of time with poets--he's married to one--and has a deep appreciation for poetry, and seemed genuinely interested in what I was doing and the particular resources I as a poet might bring to writing a novel. My taste in fiction is very compatible with his: I revere Sebald and early Ondaatje, and though I hadn't before encountered the Saterstrom book I was drawn in by its unusual form, or forms.

"Histories" isn't for me the most compelling title for a fiction course; if I had any doubts about choosing it, it's because I don't think of myself as someone who is particularly interested in historical fiction. I would much rather engage with noir or SF. But the class reinvigorated the genre for me; it was approached in such a thoughtful way, and of course the model texts on offer were incredibly rich: in addition to the titles above we also looked at excerpts from Patrick Ourednik's Europeana, Toni Morrison's Beloved (such a strange book, such an unlikely candidate for mainstreaming, yet there it is, fully canonized), Lorine Niedecker's poem "Lake Superior," and one ringer: Tracy Chevalier's Girl with a Pearl Earring (a not-bad movie but from the looks of the prose utterly bogus and banal).

Jaime Enrique reads from his forthcoming novel about the life of Cervantes.

One of the most effective exercises Laird gave us was designed to confront us with what he called "the hobnailed boot problem"; that is, the often false-seeming or distracting images and details that writers of historical fiction toss into their writing to create that sense of the past. While we did some freewriting on a scene from the past, Laird intoned a few keywords that we had to wrestle with, though we weren't required to incorporate them into the text: "goblet," "Catherine of Aragon," all that great old Medieval Times-type malarkey. I much approved of his general technique as a teacher, which was to get us writing and then to throw a monkey-wrench into the process designed to momentarily estrange one from the task of assembling a mimesis and be confronted by what we were writing as language, material for working and reworking.

I am increasingly convinced that the most interesting fiction is not that which produces the most vivid representation of reality, but which puts mimesis in tension with words and the systems native to words (sentences, paragraphs). One of the books I devoured when not in class, though Laird didn't assign it, was Ronald Sukenick's Narralogues: a loose, sometimes irritating collection of stories with a provocative thesis: that fiction should not be considered as a mode of mimetic art at all, but rather as rhetoric. The goal of this rhetoric, furthermore, is truth: not Platonic truth (which representation will always fail to produce) but truth nevertheless (Sukenick deliberately allies himself with Plato's old enemies the Sophists). A novel is successful not because it represents reality accurately but because it persuades you, not necessarily to any action but of the truth-content of the novel's form. I find much to recommend this theory; not only does it provide a better or more interesting description of what some of the greatest fictions accomplish (Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Woolf and Kafka come to mind) but it brings fiction closer to poetry.

While all this was going on--and while I was discovering that my novel is in many senses historical, from its evocation of May '68 in Paris to its preoccupation with the theater of memory--a ferment of talks and readings, as well as a dozen other workshops were happening. Really, when I was researching the various summer writing workshops out there, there was nothing else to compare in terms of the diversity, rigor, and sheer creativity of the faculty: Charles Alexander, Junior Burke, Julie Carr, Linh Dinh, Steve Evans, Thalia Field, Ross Gay, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Laird Hunt, Stephen Graham Jones, Bhanu Kapil, Joanne Kyger, Jaime Manrique, Jennifer Moxley, Jennifer Scappettone, David Trinidad (and that's just for Week One!). Many of the people on this list are acquaintances and friends, and after some momentary hesitation on my part I was glad to find myself included in a number of intensive and convivial gatherings.

A purple pair: Jen Scappetone and the legendary Anne Waldman.

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

On Not Rethinking Poetics

This is a week I've devoted to the possibilities of prose, and I am animated and inspired by a diverse constellation of texts, including:

- Ronald Sukenick's Narralogues: Truth in Fiction, acquired today, which in its introduction provides the most liberating theoretical approach to fiction that I've ever encountered, and which does a far better job of articulating my discontents and hopes than I have. Briefly, Sukenick argues for fiction as a mode of rhetoric rather than a mode of mimesis, a linguistically self-conscious investigation that seeks to persuade the reader of its truth. It's an inclusive and exciting definition that brings the work of fiction much closer to what I've always thought of as the work of poetry.

- Jeremy M. Davies' novel Rose Alley. The prose is ferociously funny and alive. Check out this excerpt to see what I mean.

- Two classic texts on the iPad: Ulysses, natch; in honor of Bloomsday I sat down this morning and reread most of the Lotos Eaters chapter. Charlotte Bronte's Villette has also been giving me a great deal of pleasure. Here's Lucy Snowe, the narrator, reflecting on her mental disposition: "I seemed to hold two lives--the life of thought, and that of reality; and, provided the former was nourished with a sufficiency of the strange necromantic joys of fancy, the privileges of the latter might remain limited to daily bread, hourly work, and a roof of shelter." What is a writer but someone who insists on merging those lives?

- Roberto Bolano's Antwerp. Yes, yes, I know, you've heard enough about Bolano. But this is an extraordinary book, just 78 pages long, the first fiction he ever wrote and therefore very close to poetry. Each chapter is just a page or two in length, consisting of highly paratactic sentences that gradually evolve a sinister narrative or narrative-feeling about sinister goings on at a low-rent resort in Spain. As a back page blurb has it, "Antwerp can be viewed as the Big Bang of Bolano's fictional universe: all the elements are here, highly compressed, at the moment that his talent explodes." Apparently Publisher's Weekly decried the book's publication as opportunistic dregs-digging, but I think it's a minor masterpiece, evocative of dread. In Sukenick's terms, it's a persuasive argument for Bolano's terrifying and elegiac vision of the dream that is literature. "Strange necromantic joys," indeed.

- Bhanu Kapil's Incubation: A Space for Monsters. I've only just begun this but it looks to be another hallucinatory sui generis narrative that plays, with a high degree of lyric intelligence, with the ideas of the monstrous and the cyborg (a la Harraway) in particular relation to the fate of Laloo, an immigrant from Punjab/London/here/there. I might assign it for my fall Frankenstein course.

Even as I fall happily down the rabbit-hole of prose, finding it at once closer to poetry than I'd hoped and stranger and more diverse than I could have imagined, my attention is diverted by talk about the "Rethinking Poetics" conference just concluded at Columbia University. Much of this talk, alas, is happening on Facebook, which only serves to reinforce the urgency of the central question that the conference seems to have raised among participants and non-participants alike: who is the poetic "we"? (I can't help but be reminded of the old joke about the Lone Ranger and Tonto surrounded by Comanches; the Masked Man says, "Looks like we're in big trouble," and Tonto replies, "What do you mean 'we,' white man?) Put another way, is there a usably coherent "we" that encompasses all the strains of contemporary innovative poetry, academic and non-, regional and conceptual, abstract lyric and flarf?

A number of conference attendees, and quite a few people who didn't attend, have complained about a sense of exclusion; I won't speak to that, since I wasn't there. (For the reports of some people who were there, see Kasey Mohammad's post-conference thoughts and John Keene's beautifully digressive "poem-report." Hopefully a few more reports will emerge from behind the Facebook firewall soon. ADDENDUM: Stephanie Young has posted a lengthy and heartfelt report that, among other things, takes on Facebook directly: REPOPORT.) But I am interested in this question of "we," especially given this week's experimental immersion in a prose reality that has created for me a temporary sense of distance of poetry and my identity as poet. I am here, really, to try and grow that identity, to make it unruly, so that "poet" and "writer" infect and inflect each other.

Sukenick, or one of his characters, makes the following claim:

"There is no outside any more. Electronics have done away with that kind of spatial metaphor, and even temporal conceptions essential to an avant-garde movement have been annulled in the electrosphere. On the Internet it doesn't matter where you are or when you are."

This is a little too simple--as noted, much of the conversation and complaint about the conference is happening on Facebook, within a virtual network that you have to be "inside" to even be aware of. But it does seem highly relevant to the anxiety that some of the conference's critics are expressing. There is still a lot of institutional energy and cultural capital concentrated in what we can't help but continue to call "the School of Quietude," but it's dissipating fast; a stream of that capital flows steadily into "our" coffers, and yet there's a sense many of us have that the whole game is up. Universities may not exist in their present form for much longer, and seem to be shedding their capacity for the accumulation and distribution of capital nearly as quickly as Big Publishing has. Ironically, the more corporate these institutions become, in a series of moves rationalized as essential for their survival, the less influence they have on our attentions and appetites. The "inside," in other words, is as archaic a category as "outside," though individual insiders and outsiders persist.

There is a fellowship of sorts among poets of the former outside (a phrase as empty and redolent as "post-avant), but is it a community? Individual friendships and affiliations are more persistent and powerful, it seems to me, than the "we" at present, and that may not be a bad thing. "We" has been defined, perhaps inadvertantly by the shutdown of the Poetry Foundation's blog, as something that happens on Facebook, where the pronoun becomes as wavery and false as the word "friend" once it's become a verb. I have Facebook "friends" who don't speak to each other, but who might nevertheless catch glimpses of each other's comments and activities through the medium of the virtual "me." This can be awkward at times but it's real as the social is real.

"Demented and sad, but social." The Facebook "We" of poetry is not, thank God, poetry. There are other forms and modes of filiation, and contra Sukenick, place and region are still important and vital. It is incumbent on me, I believe, to build stronger connections with my fellow Chicago poets, even as I remain part of a larger thing (cosa nostra?) without geographic boundaries and, hopefully, with ever-weakening boundaries as defined by class, ethnicity, education, etc. Readings and talks and panels, academic or non, continue to be crucial, though as Thalia Field suggested yesterday the truest companionship is in the work. And I can be friends with poets who don't share my particular poetics (hi, Chris!), and I can be socially awkward with poets I deeply admire. There are multiple strands and crossings, and arguing can or ought to be compatible with liking. Arguing and liking are both life, values, poetics.

Back to prose, for a few more days anyway. Let poetics take care of itself, and let poets take care.

Thursday, June 10, 2010

Technical Difficulties, or My So-Called E-Life

First, an announcement: if you read this blog, you probably have a brilliant manuscript of poems lying around. Dust it off and send it to Apostrophe Books for their open reading period. They're reading manuscripts between June 1 and August 31. Read their submission guidelines here, and check out the brilliant books they've published by the likes of Catherine Meng and Johannes Göransson here.

&&&

I've been Twittering for about a month now, and find that it in no way replaces blogging or any other long-form writing. The big discovery has been less in creating my own tweets--though the 140-character limitation does appeal to my interest in constrained literature--and more in following the tweets of others. It's fascinating to move out of the "friends" paradigm of Facebook into a much wider world, so that tweets from institutions like WBEZ and the Poetry Foundation are cheek by jowl with tweets from Sarah Silverman, HTML Giant, Bookforum, and Roger Ebert. I like how much more open it feels than Facebook, plus you don't have the creepy privacy issues to worry about.The other recent digital innovation in my life is the iPad. The rap on the iPad (aside from worrisome questions about the suicide sweatshops in which they're manufactured) is that it's only useful for consumption, rather than production--not only that, but you're consuming within the airtight digital economy regulated by Apple. The first part of this critique is overblown: the iPad is more than functional for light emailing, Twitter, et al, and if I were to spring for a separate keyboard I could happily write on the thing. I would just need a better stand than the crappy strip of plastic that came with the neoprene case I bought at Best Buy--don't make that mistake.

What I have thought hard about is the viability of the iPad as an ereader, and the question of electronic books generally. So far, reading books on the machine is a mixed bag. I don't mind the backlit screen--the iBooks app presents prose beautifully, and Amazon's Kindle app does nearly as nice a job--plus the Kindle has a much greater diversity of books available, including scholarly books which are non-existent in the Apple-controlled universe. But an average price of $10 seems far too high to pay for a virtual book that you can't lend out and can't even be sure of keeping for more than a few years, given the rapid evolution of digital platforms (plus there's the possibility, even the likelihood, of censorship to contend with).

The iBooks app is, at present, hopeless with poetry: when I downloaded a sample of John Ashbery's Notes from the Air all the lines were inexplicably double spaced. A program like iBooks is premised upon the fungibility of prose: each "page" of the book you're reading is subject to radical transformation based on the orientation of the iPad (a single big page like that of a hardcover or two smaller pages like those of a paperback) and the size of the font you choose (this also increases or decreases the number of "pages").

The Kindle app did a somewhat better job of preserving the look of the poems on the page. But the poems with the longest lines presented some awkward rollover issues mitigated only by turning the page into landscape mode (and I am sentimental enough to be attracted to the way iBooks simulates the look of a printed page, which the Kindle app is less successful at doing). The most serious drawback to either platform, however, is the general unavailability of books from small presses: if your primary access to literature comes only through the big New York publishers you hardly have access to literature at all. (There is also a very limited selection of books in translation, but this is hardly a problem confined to e-readers.)

That said, the iPad is proving to be an ideal device for reading poetry: not poetry books as such, but poetry in electronic form. It is far more intuitive and intimate to read poems published in electronic journals such as Action, Yes (check out the latest issue, btw) on the iPad than it is with a laptop or desktop screen. I've never liked reading poems on the Web before--the endless scrolling with mouse or down arrow is distracting and clumsy, and the horizontal orientation of computer screens is ill-suited to the vertical energy of most poems. But scrolling through poems on the iPad in vertical orientation feels as natural to that medium as turning pages is to the medium of the book. It's also brilliant for PDFs, which I've never enjoyed reading on screens and usually have to print out in order to really engage with them. Poetry books and chapbooks in PDF form (such as Tina Darragh and Marcella Durand's collaboration Deep eco pré) are accessible in a new way, and that speaks of very exciting possibilities for the electronic publication and distribution of poetry. Ultimately ebooks and epoems will become their own media, not simply a means of transmitting an experience inevitably different from if not necessarily inferior to the experience of print.

There's a lot of talk these days about the changes that the Web might be making to our brains, turning us all into ADD hunter-gatherers of data and disattuning us from the long rhythms of textual immersion that many critics associate with that perennially dying nineteenth-century literary form, the novel. I do worry about the culture of distraction and the effects it might be having on my own brain. I live a thoroughly wired life: multiple laptops, an iPhone, now the iPad. I am never out of touch with the hive mind. This isn't so much a problem with writing: for better or worse, I am now a thoroughly hypertextual writer, at least when writing here or producing academic prose. I flip constantly back and forth from the document I'm writing to web pages and PDFs, in a peculiar halfway state of mind between research and distraction. But it is harder for me to concentrate on books than it used to be. And one of the reasons I began writing my novel in longhand, I now realize, was to get away from the distractions of the Web. I write poetry on paper for much the same reason. Perhaps the fiction or poetry I could write on the computer wouldn't be worse than the writing I do with a pen, but there is a difference, and I don't know how perceptible that difference might be to readers.

I do my best and most concentrated work in coffee shops and other busy places: the effort of tuning out the aural and visual stimuli of other people helps me attune to the task at hand. In a private space like my office at school I become hungry for stimuli, and so waste what feels like hours with politics blogs and YouTube. It's possible that the new diversity of Internet gadgets might actually help me in this regard: in my office, I could disconnect my computer from the Internet and keep the iPad handy for any Web searches or emails I needed to write. Then the computer could once again become a simple tool for writing, as opposed to an irresistible nexus of stimuli, and the iPad would be more like the stack of books I usually have at my side when I'm writing something.

&&&

This will probably be my last blog post until I land in Boulder, Colorado on Sunday to take part for one week in the Summer Writing Program at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics (man, that's fun to type, though I really think it would be more progressive of them to change it to Embodied Poetics). I'm taking a fiction class with Laird Hunt; it will be strange and I hope energizing to be a student again after all these years. After that I'll be spending a week in Arizona (should I bring my passport?) with family before returning to Chicago and the secret poetry project I'll be prepared to reveal at summer's end.

Tuesday, June 01, 2010

Aqualung

What it comes down to - my extravagant claim that "only poetry can counter the Big Lie of power" - is the peculiar status of poetry's medium, words. They are not material, though they have the material properties of sound, appearance, and history. Nor are they wholly conceptual or transparent vehicles for reference. This is what makes it possible for poetry to do more than describe--to go beyond the judicious study of the reality-based community. Poetry creates connections in language with the potential to restructure perception and to stimulate new thinking. If the language of empire is lethally performative--turning the disaster in the Gulf into an interesting technical problem with its own anesthetizing vocabulary ("top kill," "junk shot," "relief well"), or the Gaza flotilla raid into "military acts of defense"--poetic language performs deterritorialization, creating new configurations which invite thought, perception, realization.

Marcella Durand puts it more eloquently than I do at the conclusion of her essay "The Ecology of Poetry," found in the anthology I am currently devouring, Brenda Iijima's eco language reader:

Most other disciplines, such as biology, oceanography, mathematics are usually obliged to separate their data and observations into discrete topics. You're not really supposed to link your findings about sea birds nesting on a remote Arctic island with the drought in the West. But as a poet, you certainly can. And you can do it in a way that journalists can't—you can do it in a way that is concentrated, that alters perception, that permanently alters language or a linguistic structure. Because poets work in a medium that not only is in itself an art, but an art that interacts with the exterior world—with things, events, systems—and through this multidimensional aspect of poetry, poets can be an essential catalyst for increased perception, and increased change. (124)Durand claims for poetry the territory that my Lake Forest colleague Glenn Adelson calls "hard interdisciplinarity": the blending and blurring of interdisciplinary lines of study and knowledge-production in a rigorous and demanding way. At the same time, poetry is itself a discipline, preoccupied as Durand says with "systems" made up in language:

Experimental ecological poets are concerned with the links between words and sentences, stanzas, paragraphs,, and how these systems link with energy and matter—that is, the exterior world. And to return to the idea of equality of value, such equalization of subject/object-object/subject frees up the poet's specialized abilities to associate. Association, juxtaposition, and metaphor are tools that the poet can use to address larger systems. (123)It's not a coincidence that Durand's claims for poetry, which are nearly as extravagant as my own, are linked with ecology, which is or ought to be the interdisciplinary discipline of our time. Poetry and ecology fit well together because both investigate systems and systematicity without themselves being systems, using specialized tools that are neither wholly empirical/material nor wholly theoretical/conceptual.

But ecology, like poetry, has a problem: in spite of its interdisciplinary character, it's still, well, hard. And the ecological narrative seems to have all but foundered in recent years, as persuasively argued in a controversial article, "The Death of Environmentalism," available for perusal at Grist.org. Ecology and environmentalism have not persuaded the mass of people of the essential truth of interconnectedness; they have not undone the poisonous, fundamentally pastoral narrative of "nature" as something outside of and separate from us. Whether you see "nature" as something to be exploited, managed, or protected, that implicitly hierarchical structure of separation is the crumbling pillar that upholds our entire technological civilization. The myths of the wilderness and the garden, then, are just as limiting and destructive to the new thought we need as the countervailing narrative that makes ecology (literally, "home knowledge," oikos logos) a sideshow to economy ("home management").

The title of this post refers to another Jethro Tull song; I'm not interested in the lyrics this time (about a dirty old man leering at schoolgirls) but the old-fashioned name for an oxygen tank for underwater exploration, which makes it possible for creatures of air and land to experience another element. A modern aqualung is a rebreather, which Wikipedia tells us is a more efficient and economical form of breathing equipment that recycles the user's own breath while adding oxygen to the mix; this creates less "noise" in that the user generates few bubbles, which on the one hand is less disruptive to marine life and permits closer observation, and on the other hand is useful to military commandos because it allows them to approach the enemy undetected.

Poetry, then, is a kind of aqualung or rebreather, recycling available words and discourses while adding something new and potentially life-giving to the mix. It enables the ecological thinking that we so desperately need now. It makes, in spite of postmodernism, the rediscovery of depths possible. And, I maintain, it's this kind of thinking with/through/to "things as they exist" (Zukofsky, "An Objective") that can counter the discourses of power.

****************

The dark coincidence of my turn to Leslie Scalapino and her recent passing has not escaped me. I'm saddened that my rediscovery of her work must take place without her actually being and writing in the world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Popular Posts

-

This is gonna be a loooooong post. What follows is a freely edited transcription of my notes from the Zukofsky/100 conference at Columbia t...

-

Midway through my life's journey comes a long moment of reflection and redefinition regarding poetics (this comes in place of the conver...

-

Will be blogging more or less permanently now at http://www.joshua-corey.com/blog/ . Or follow me on Twitter: @joshcorey

-

My title is taken from the comments stream of an article recently published by The Chronicle of Higher Education , David Alpaugh's ...

-

Elif Batuman has amplified her criticism of the discipline of creative writing (which I've written about before ) in a review-essay that...

-

Thursday, September 29, 2011 Berlin. Fog of sleep deprivation coloring an otherwise perfect blue autumn day a sort of miasmic yellow i...

-

Trained it down to DePaul's Loop campus this morning to take part in a panel, "Why Writers Should Blog," alongside Tony Trigil...

-

In one week Lake Forest will hold its commencement and I'll take off my professor's hat for the summer. A few weeks later, in June, ...

-

Farewell, Barbara Guest .

-

It is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. [1] Begin again. In a new spirit ...