Wednesday, June 30, 2010

The Trial

Monday, June 28, 2010

From a Notebook (July 2009)

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

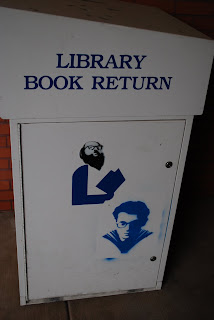

Book Return: Notes from Naropa

For one solid week I took leave from my family and from my identity as poet to be a student in Laird Hunt's fiction workshop at Naropa University's Summer Writing Program. I arrived on Sunday afternoon filled with a mixture of excitement and nigh-existential nausea, such as I imagine afflicts secret agents. What would it be like to begin at the beginning--to sit at the seminar table and not be running the seminar--to be an unknown quantity in a tight-knit and storied community--to have so many poetry friends and acquaintances on the faculty while I went as a paying customer?

Historical figures like Herodotus, Hannibal, Jesus of Nazareth, and Calamity Jane have all served as energy nodes around which writers have built significant works of prose. We’ll examine texts like Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter, Selah Saterstrom’s The Pink Institution, and W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn to explore that prose which, if we can kick awake that poor overworked pearl, posits the historical as its grain of sand. Students will produce their own writings for consideration and helpful critique.

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

On Not Rethinking Poetics

- Ronald Sukenick's Narralogues: Truth in Fiction, acquired today, which in its introduction provides the most liberating theoretical approach to fiction that I've ever encountered, and which does a far better job of articulating my discontents and hopes than I have. Briefly, Sukenick argues for fiction as a mode of rhetoric rather than a mode of mimesis, a linguistically self-conscious investigation that seeks to persuade the reader of its truth. It's an inclusive and exciting definition that brings the work of fiction much closer to what I've always thought of as the work of poetry.

- Jeremy M. Davies' novel Rose Alley. The prose is ferociously funny and alive. Check out this excerpt to see what I mean.

- Two classic texts on the iPad: Ulysses, natch; in honor of Bloomsday I sat down this morning and reread most of the Lotos Eaters chapter. Charlotte Bronte's Villette has also been giving me a great deal of pleasure. Here's Lucy Snowe, the narrator, reflecting on her mental disposition: "I seemed to hold two lives--the life of thought, and that of reality; and, provided the former was nourished with a sufficiency of the strange necromantic joys of fancy, the privileges of the latter might remain limited to daily bread, hourly work, and a roof of shelter." What is a writer but someone who insists on merging those lives?

- Roberto Bolano's Antwerp. Yes, yes, I know, you've heard enough about Bolano. But this is an extraordinary book, just 78 pages long, the first fiction he ever wrote and therefore very close to poetry. Each chapter is just a page or two in length, consisting of highly paratactic sentences that gradually evolve a sinister narrative or narrative-feeling about sinister goings on at a low-rent resort in Spain. As a back page blurb has it, "Antwerp can be viewed as the Big Bang of Bolano's fictional universe: all the elements are here, highly compressed, at the moment that his talent explodes." Apparently Publisher's Weekly decried the book's publication as opportunistic dregs-digging, but I think it's a minor masterpiece, evocative of dread. In Sukenick's terms, it's a persuasive argument for Bolano's terrifying and elegiac vision of the dream that is literature. "Strange necromantic joys," indeed.

- Bhanu Kapil's Incubation: A Space for Monsters. I've only just begun this but it looks to be another hallucinatory sui generis narrative that plays, with a high degree of lyric intelligence, with the ideas of the monstrous and the cyborg (a la Harraway) in particular relation to the fate of Laloo, an immigrant from Punjab/London/here/there. I might assign it for my fall Frankenstein course.

"There is no outside any more. Electronics have done away with that kind of spatial metaphor, and even temporal conceptions essential to an avant-garde movement have been annulled in the electrosphere. On the Internet it doesn't matter where you are or when you are."

Thursday, June 10, 2010

Technical Difficulties, or My So-Called E-Life

The other recent digital innovation in my life is the iPad. The rap on the iPad (aside from worrisome questions about the suicide sweatshops in which they're manufactured) is that it's only useful for consumption, rather than production--not only that, but you're consuming within the airtight digital economy regulated by Apple. The first part of this critique is overblown: the iPad is more than functional for light emailing, Twitter, et al, and if I were to spring for a separate keyboard I could happily write on the thing. I would just need a better stand than the crappy strip of plastic that came with the neoprene case I bought at Best Buy--don't make that mistake.

What I have thought hard about is the viability of the iPad as an ereader, and the question of electronic books generally. So far, reading books on the machine is a mixed bag. I don't mind the backlit screen--the iBooks app presents prose beautifully, and Amazon's Kindle app does nearly as nice a job--plus the Kindle has a much greater diversity of books available, including scholarly books which are non-existent in the Apple-controlled universe. But an average price of $10 seems far too high to pay for a virtual book that you can't lend out and can't even be sure of keeping for more than a few years, given the rapid evolution of digital platforms (plus there's the possibility, even the likelihood, of censorship to contend with).

Tuesday, June 01, 2010

Aqualung

What it comes down to - my extravagant claim that "only poetry can counter the Big Lie of power" - is the peculiar status of poetry's medium, words. They are not material, though they have the material properties of sound, appearance, and history. Nor are they wholly conceptual or transparent vehicles for reference. This is what makes it possible for poetry to do more than describe--to go beyond the judicious study of the reality-based community. Poetry creates connections in language with the potential to restructure perception and to stimulate new thinking. If the language of empire is lethally performative--turning the disaster in the Gulf into an interesting technical problem with its own anesthetizing vocabulary ("top kill," "junk shot," "relief well"), or the Gaza flotilla raid into "military acts of defense"--poetic language performs deterritorialization, creating new configurations which invite thought, perception, realization.

Most other disciplines, such as biology, oceanography, mathematics are usually obliged to separate their data and observations into discrete topics. You're not really supposed to link your findings about sea birds nesting on a remote Arctic island with the drought in the West. But as a poet, you certainly can. And you can do it in a way that journalists can't—you can do it in a way that is concentrated, that alters perception, that permanently alters language or a linguistic structure. Because poets work in a medium that not only is in itself an art, but an art that interacts with the exterior world—with things, events, systems—and through this multidimensional aspect of poetry, poets can be an essential catalyst for increased perception, and increased change. (124)Durand claims for poetry the territory that my Lake Forest colleague Glenn Adelson calls "hard interdisciplinarity": the blending and blurring of interdisciplinary lines of study and knowledge-production in a rigorous and demanding way. At the same time, poetry is itself a discipline, preoccupied as Durand says with "systems" made up in language:

Experimental ecological poets are concerned with the links between words and sentences, stanzas, paragraphs,, and how these systems link with energy and matter—that is, the exterior world. And to return to the idea of equality of value, such equalization of subject/object-object/subject frees up the poet's specialized abilities to associate. Association, juxtaposition, and metaphor are tools that the poet can use to address larger systems. (123)It's not a coincidence that Durand's claims for poetry, which are nearly as extravagant as my own, are linked with ecology, which is or ought to be the interdisciplinary discipline of our time. Poetry and ecology fit well together because both investigate systems and systematicity without themselves being systems, using specialized tools that are neither wholly empirical/material nor wholly theoretical/conceptual.

****************

The dark coincidence of my turn to Leslie Scalapino and her recent passing has not escaped me. I'm saddened that my rediscovery of her work must take place without her actually being and writing in the world.

Monday, May 24, 2010

Merrill Gilfillan, from The Seasons

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Thick as a Brick

I

Reading one of the thorniest and most interesting exchanges in Firestone and Lomax's Letters to Poets: Conversations about Poetics, Politics, and Community, between Judith Goldman and Leslie Scalapino. (A modified excerpt from the correspondence is available here.) It kicks off with a 2004 letter from Scalapino in which she tries to explain her own poetic practice and how it relates to a subject which has not lost any urgency since that long-ago election year: "the relation of writing to events." That deceptively simple phrase encapsulates the question/declaration perennially phrased as "Poetry makes nothing happen" (Auden) / "No one listens to poetry" (Spicer) / "Can poetry matter?" (Dana Gioia, et al) and two more recent responses to the same anxiety: Stephen Burt's gently deprecating "Art vs. Laundry" and Alan Davies' fiery "The Dea(r)th of Poetry" (it doesn't surprise me to learn that Davies' father was a preacher). I also have in mind my colleague Bob Archambeau's recent

posts on the Cambridge Poets and the exaggerated claims sometimes made for the political efficacy of their work. Elsewhere this anxiety gets expressed in vitriol directed toward MFA programs / Internet culture / youth. But the Goldman/Scalapino dialogue suggests an alternative to codgerish despair on the one hand and triumphant insularism on the other.

In the course of their correspondence, Goldman and Scalapino touch on the infamous remarks on "the reality-based community" that Ron Suskind elicited from an anonymous high official in the second Bush administration, worth requoting here:

The aide said that guys like me were "in what we call the reality-based community," which he defined as people who "believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality." I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. "That's not the way the world really works anymore," he continued. "We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors… and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do."

I still get a chill from the barefaced arrogance that radiates from what Goldman calls "the (psychotic) state of self-grounding, unpuncturable, unrevisable self-confidence in Bush's cohort." It's pungent evidence, if more evidence were needed, of the ethical bankruptcy of postmodernism in its purest forms, akin to the news about the Israeli army's incorporation of the theory of Deleuze and Guattari into their urban warfare strategies.* But the response to this is not, cannot be any sort of return to first principles, enlightenment-vintage or otherwise. There is no democratic instrument for the imposition of values; only individuals can be motivated to recall themselves to thinking, and only individuals can choose to enter the bonds of solidarity that can bring about change.

The preoccupation of writers and intellectuals is or ought to be that function that writing is better equipped to perform than any other art form: to recall readers to the act of thinking. Scalapino makes that point in her first letter to Goldman. She first draws a distinction between what she sees herself as doing and what "the poets near to me" (aka the Language poets) were doing: trying "to consider relation of 'being' to history.' On the one hand, events one does (and events in the world) are not the being (are not one). On the other hand, 'to fall out' of these events in the world… is not to be at all, not to have ever been."

"Being," then, stands in history without being of it, yet to step out of that history—to take the observer's position—is to not be at all (one's being may be at its most ideological when one does not act). That's the moment in which poetry becomes the poetry that makes nothing happen: the poet observes, stands outside, and describes:

Descriptive language is an example of "falling out of" (or never having been in, always separate from) one's own motions described there. Such as: to describe events or to reference ideas already in place or to discuss other people's ideas, rather than one's writing being the act of thinking, an action that would also be an invention occurring there. Sometimes poets (I noticed this in the 80s) would reject even writing a thought process (at all), taking this for descriptive rather than the act of thinking.

This is an incisive critique of what Charles Altieri calls "the scenic mode" in American poetry: a poetry that describes the world, however elegantly or with whatever degree of rueful poignancy, does not bring any pressure of thought on the world; it is not "an invention occurring there." For Scalapino this "invention" takes place on the level of syntax, a form of movement different from yet related to—in a non-representational way—the movement of bodies, which is the ground of action and history. "I wanted the writing to be that gap: the writing being life, real-time minute motions (physical movements or events) but being or are these (minute motions) as syntax (not representation of the events)." She defines her poetic syntax alternately as "a sound-shape which is… creating alternate interpretations" and as "memory trace or conceptual shape."

The strangeness of Scalapino's syntax (a brief example) keeps pushing the reader away from representation or narrative and into the multifoliate gap between writing/being/representation/history, a gap which under ideal circumstances we are led to think our way into and through and out of. But here is where I re-encounter Spicer's "No one listens to poetry," because that syntax is under such pressure that it either defies comprehension or becomes purely formal (it's the same thing), so that the truth-content of the poem eludes the reader. This is where, for me, lyric comes back into the equation: beauty or buzz can seduce the distracted reader into entering that gap between word and world—that vibrating force field unique to the poetry that dislocates speech and representation. And yet I'm cognizant of the danger that the field itself, its hum, can become mere sensation—that my default mode for responding to a poem, even a "difficult" poem, is aesthetic delectation. Thought comes later, and—I'll be honest—sometimes doesn't come at all. The poem can resist my intelligence wholly successfully, and I'll still enjoy it, as long as it stimulates me not to thought (hypostasis, noun-state) but to thinking (the only verb that connects being with becoming).

Scalapino's practice, like almost everything avant-garde, is a mode of collage, which emphasizes the disordering or de-hierarchizing of elements over the magpie bricolage of unlike elements. It's a bit like the difference between atonal music's dethronement of melody—which can sound like the untrained ear like an attack on music itself—and the DJ's mash-up that renders familiar sounds strange (what Danger Mouse did in The Grey Album) and turns unfamiliar unmusical sounds into something you can dance to (D.J. Spooky). It's a mode of what I call intensive collage—it breaks inward—as opposed to extensive collage. To put it another way, collage is a mode of deterritorialization, but whereas extensive collage in the mode of Pound and Olson is often didactic and reterritorializing, intensive collage at its purest maintains multiple possibilities as multiple, so that any strong interpretive move made by the reader toward "meaning" is to miss the point, which is to be in the thinking that makes the poem. Scalapino writes:

It means that anything occurring impinges on and alters everything else—equally effective in the sense of large and small are part of the context. There's no hierarchy (in existence), though it occurs socially created and created by animals, authority does not derive from it. The writing enables one to see that and be 'without' it. A poem can be a terrain where hierarchy can be undone or not occur (in the writing), but obviously the writing does not make it not occur in the world. So, its subject is also the relation of conceptual to phenomena, conceptual being an action also. Yet even proposing conceptual non-hierarchy frequently meets with great resistance (usually).

What has this got to do with the relation of poetry to events? Perhaps only that that relation is thinking, a mode of cognition that, as Heidegger suggests, is very close to the poetic, and fundamentally different from the discursive language that envelops "judicious study of discernible reality." It may be the only hope that people without power—subjects or subalterns of empire—have of anticipating, resisting, and reimagining the violent redescription of the world. Though it should go without saying that this imaginative and de-hierarchizing mode of thought is insufficient without actual political action, actual solidarity, actual resistance. But how can the latter take place without this work of the imagination?

Put another way: only poetry can counter the Big Lie of power. We've lived through a decade in which reasonable and intelligent and empirically acute people—God bless 'em—pointed out as strenuously and as often as possible that the emperor had no clothes. And it seems to have done almost no good at all. All we got were some scathingly accurate and politically ineffectual descriptions of a reality that the empire had already moved on from, just as Bush's Rasputin said.

It may seem that I'm falling into the trap of according an importance to poetry entirely disproportionate to its actual infinitesimal influence in the world. Maybe I am. But it's my hope that the poetry of collage, of deterritorialization, really is in spite of everything capable of becoming an avant-garde in the literal sense: the leading edge of discourse-formation, of new imaginative possibilities for the arrangements of words and—if only by analogy and allegory—social arrangements and structures.

II

And yet I can't content myself with the belief that it's enough that this stuff gets written and that the same people who write the stuff read it. I dream of a wider readership for poetry without compromise with the bugbear of accessibility. Some of the other writers and critics I referenced in my first paragraph have contributions to make to this possibility. I do think that if there were more and better poetry criticism out there it might build a bridge to the many highly literate people out there who read everything but poetry. Alan Davies calls for a rigor and candor in poetry criticism that is undoubtedly lacking at the moment (though I wonder if he's spent much time with The Constant Critic or the wonderfully in-depth reviews published by The Nation. Davies' essay evokes a 2009 discussion at Mayday, "Some Darker Bouquets," in which Kent Johnson and a host of interlocutors debate the role of the negative review in poetry. By far the best solution on offer, I think, is not Kent's proposal of anonymous reviews (who would write them?) but encouraging non-poets to take up the task; poetry needs the robust community of critics that nearly every other art form can claim. But this is a circular argument, for what will induce those non-poets to read poetry intensively and seriously enough to critique it? What will induce them to get some skin in the game?

The title of my post refers of course to one of my guilty pleasures: the eponymous prog-rock concept album released in 1972 by Jethro Tull. Written and performed with tongue firmly in Ian Anderson's cheek, the album features deliberately abstruse, pretentious, quasi-sensical lyrics that were one of my first introductions, as a teenager, to the living possibilities of poetic language. I have always been haunted by the title track, which manages to evoke both of the Lears (the King and Edward):

Really don't mind if you sit this one out.

My words but a whisper -- your deafness a SHOUT.

I may make you feel but I can't make you think.

Your sperm's in the gutter -- your love's in the sink.

So you ride yourselves over the fields and

you make all your animal deals and

your wise men don't know how it feels to be thick as a brick.

I feel this is as eloquent a statement as any of the dilemma of the artist who wants his audience to think, but whose means of doing so—the sensuality of materials like words and narratives and musical notes—are incommensurate with thinking. The energies of the "you" addressed by the singer are dismembered and sterile, and the discursive knowledge of "your wise men" cannot capture how it feels to be thick as a brick—to be in the gap between being and becoming, the gap of not-knowing. How it feels—because this thinking, this conceptual activity that collage writing demands of the reader, is a feeling. The trouble is, to most readers, it feels an awful lot like feeling stupid. Whereas those of us who have habituated ourselves to these forms dare to be stupid (to pull another déclassé musical reference out of my hat) and feel not-knowing as an exhilaration, an ecstasy that returns us, momentarily, to being.

Poetry must be in a desperate situation indeed if I'm turning to Jethro Tull, right? But my point is that people want to feel something when they read, and that poetic thinking is a feeling—is an aesthetic experience in its own right, akin to the sublime. One is in the presence of the ungraspable, your deepest imaginative powers—the Romantics called it Reason—stretched and exercised by the experience. The extensive poem—remnant epic—puts us in contact with the terror of connection—makes perceptible the logic of the world (of capital) that our media are designed to distract us from, without necessarily succumbing to the logic of paranoia and the conspiracy theory. The intensive poem, whose logic is fundamentally lyric, connects us with something more elusive; like Eliot's shred of platinum it catalyzies a reaction between body and soul, feeling and thinking, being and becoming.

And yeah, parts of that album are frigging sublime, and I stand by that.

* For a poetic reflection on this phenomenon see Rachel Zolf's new book Neighbour Procedure, the title of which, I learn from Vanessa Place's review, "refers to an entry technique deployed by Israeli soldiers in which Palestinians are forced to break the walls inside their neighbor's houses, allowing the soldiers to move laterally between houses." Among other things, this concept puts a new and chilling spin on the title of one of my favorite Kevin Davies' poems, Lateral Argument.

Saturday, May 01, 2010

Cinematic Prose and Its Posthuman Other

I have hopes for this workshop's providing a doorway into the study of fiction, or at least of writing that includes the fictional, that will not simply reproduce the mainstream aesthetic. One of the writers I might study with is Thalia Field, quoted in my previous post, and she's come up with a useful bit of shorthand for that aesthetic that she calls "cinematic prose." At the same time I have no wish to reproduce the affectless postmodern collage aesthetic that I've encountered in my initial forays (though I do often find that work compelling, especially at its most abstract and Asperbergers-esque, as in the work of Lydia Davis or Tao Lin).

I have hopes for this workshop's providing a doorway into the study of fiction, or at least of writing that includes the fictional, that will not simply reproduce the mainstream aesthetic. One of the writers I might study with is Thalia Field, quoted in my previous post, and she's come up with a useful bit of shorthand for that aesthetic that she calls "cinematic prose." At the same time I have no wish to reproduce the affectless postmodern collage aesthetic that I've encountered in my initial forays (though I do often find that work compelling, especially at its most abstract and Asperbergers-esque, as in the work of Lydia Davis or Tao Lin).  The other class I might take will be led by Laird Hunt; I love his novel The Impossibly for the way it plays with noir conventions while inventing an abstract narrative language that constantly deflects the reader from simple identification with its narrator. Though that narrator does happen to be another affectless, Aspergers-esque figure, there's a baroque quality to the lacunae in the thriller plot that he unfolds for us that suggests something more interesting is going on than postmodern minimalism. That and what little I've seen of Hunt's other fiction suggests an appetite for something more heightened--what I think of as the operatic, which is another alternative to the cinematic.

The other class I might take will be led by Laird Hunt; I love his novel The Impossibly for the way it plays with noir conventions while inventing an abstract narrative language that constantly deflects the reader from simple identification with its narrator. Though that narrator does happen to be another affectless, Aspergers-esque figure, there's a baroque quality to the lacunae in the thriller plot that he unfolds for us that suggests something more interesting is going on than postmodern minimalism. That and what little I've seen of Hunt's other fiction suggests an appetite for something more heightened--what I think of as the operatic, which is another alternative to the cinematic.Notice how the word “frames” preserves some analogy to cinema and visual art, even as Field criticizes “cinematic point of view” for the way in which it reinforces the ideology of the rugged individualist that filmed narratives deploy. I am reminded of possibly my favorite of the five remakes of the 1967 short film The Perfect Human that Jørgen Leth directs under constraints imposed by Lars von Trier in The Five Obstructions: “The Perfect Human: Brussels.” This is the remake that Leth makes without actual constraints (or to put it another way, without von Trier’s malicious yet useful mode of collaboration), as punishment for having broken the rules in the previous version, “The Perfect Human: Bombay.” It’s an elliptical noir that deploys certain tropes of the thriller—a mysterious man on a mysterious mission, an equally mysterious and beautiful “woman,” hotels, rendezvous, evening dress, sex—while eliding and eluding the thriller plot. Its most salient feature for this discussion is the voice-over narration, in which an unseen man speculates about the film’s hero, “the perfect man.” “Who is he? I would like to know something more about him. I have seen him smoke a cigarette. Does he think about fucking?” These questions focus the viewer’s attention onto the cinematic tropism unfolding before his eyes: it is enough for a camera to follow a man through city streets and into a lobby where he asks the clerk if he has any messages for us to identify with and invest in his singularity, his protagonism (try this even more unwieldy coinage: protagon-organism). The literary device of the voice-over (which any film student will tell you is a sign of weakness, a crutch that breaks faith with the codes of visual storytelling) breaks the very “perfection” that the film, qua film, pursues.

If film can transgress its own form in pursuit of truth by incorporating the literary, Field seems to suggest that literature must dissociate itself from the cinematic if it is to break from its compulsive anthropocentrism and anthropomorphism. “Cinematic prose contains consistent scale, in space and time, and the human figure, whether in close-up or establishing shot, predominates. This aesthetic holds because ultimately we don’t spend a lot of time in the awareness of our world without ourselves as tragic heroes of it.” Instead, she suggests that "Revising our obsession with domestic psychosymbolic tragedies (set on the literary equivalent of Hollywood “soundstages”) could shake the narrow focus and force us to listen differently" to "paradoxical, poly-vocal, cacophonous" stories.

To keep this in a literary frame, you could say that Field advocates a poetics of heteroglossia over monoglossia, and that what takes her beyond Bakhtin is her desire to incorporate not merely non-literary elements and voices into her writing, but also the nonhuman. A heteroglossia of the posthuman exceeds, I think, the bounds of any cinema unless that cinema abandons narrative or even representation (think of Stan Brakhage). A radical materialism, it would seek to embody discourse (making social production discernible and available to critique), and discover discourse in the body (human bodies, animal bodies). It's no wonder that Field's second book of unclassifiable but visually poetic pieces is titled Incarnate: Story Material.

The "cinematic prose" analogy fascinates me because my own fictional investigation began with wondering what it was, exactly, that a prose fiction could do that wasn't at this stage in history a belated form of cinema. My protagonist, or one of them, is a deliberately flat, "perfect" character, very much an object for the imaginary omniscient camera to track through the plot. I am not myself ready to abandon the realm of domestic psychosymbolic tragedy; I hope rather than suppressing that element to heighten it, pushing again toward the operatic, which I would define as a mode that explores opportunities for heightened feeling, for excesses of feeling to match the excesses of language that attract me. For I am simply not a minimalist (nor am I a Buddhist practitioner of non-attachment, as Field is). As much as I admire Beckett, I imprinted early on Joyce, lovely tenor, who certainly remains inexhaustibly "paradoxical, poly-vocal, cacophonous."

It seems then, as ever, I am caught somewhere in the muddy middle between romanticism and materialism, even in my fiction writing; skeptical of humanism but not ready to embrace my inner cyborg either. Perhaps the best I can hope for is that my ambivalence will defend me from received wisdom of whatever stripe. In the meantime I'd like to borrow Field's motto, "Hello, friendly edge!" Whether or not I take her workshop, I feel she's already taught me quite a bit.

Friday, April 30, 2010

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

The Truth and Life of Myth

This past Saturday I made it down to the School of the Art Institute to catch the tail end of the Robert Duncan Symposium. It's apt, I think, that they called it a symposium rather than a conference, because the point seemed to be to celebrate and reflect on Duncan more than to criticize him. I was only able to attend the last pieces: Michael Palmer's poetry reading, and a conversation between Peter O'Leary, Joseph Donahue, and Nathaniel Mackey. But it was more than enough to stimulate a great deal of thought and reflection on my part.

On the back of the Symposium program was placed this quote from the essay from which it took its title, "The Truth and Life of Myth":

The surety of the myth for the poet has such force that it operates as a primary reality in itself, having volition. The mythic content comes to us, commanding the design of the poem; it calls the poet into action, and with whatever lore and craft he has prepared himself for that call, he must answer to give body in the poem to the formative will.

I have a lot of resistance to Duncan, which centers on my resistance to myth and magick and the occultist claims he and his circle were inclined to make about poetry. I'm too much a child of the Enlightenment not to be repelled by the figure Duncan cuts as a seer: he really puts the mystification into mystic. Yet I find many of his poems profoundly moving, and even appropriated "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow" as an epithalamium to be read at my wedding, recentering the quest it describes for originary creative power (which necessarily brushes up against darkness and the demonic) inside that most mythic and everyday of ritual constructs, marriage. So profound ambivalence is what I carry into any encounter with Duncan as bearer of the part of the Modernist tradition that engages most profoundly with myth and hermetic knowledge, as opposed to the Modernism of cultural critique and collage which I find a far more congenial site of engagement.

Ron Silliman, an anti-Duncan if ever there was one (really, the entire Language tradition is against Duncan), once wrote perceptively if polemically about how the hermetic knowledge that Duncan and his circle used as an armature for poetry had been supplanted by Silliman's generation by Marxism and post-structuralism. And it was thinking about this, as first I listened to Palmer read and then to the conversation with Mackey, that has helped me to articulate my discomfort and fascination with the place of myth in poetry. For the poet, myth is a form of capital, and too often the Modernist engagement with myth has looked to me like a form of primitive accumulation, given that form of capital acquisition's reliance on enclosure. That is, the desire to create a hermetic circle, open only to initiates, has the effect, intentionally or not, of excluding those with no knowledge (literally, no investment) in the fate of Osiris or who Aleister Crowley was or ritual sacrifice in ancient Sumeria or whatever. It all seems impossibly remote from how life is actually lived. And, if you're at all invested in a materialist worldview, it seems less like a quest for reality than an escape from it, a shying away from the forces of social production that actually make the world.

But of course myth is not the only form of poetic capital, and the discourses of post-structuralism, as Ron observed, make a dandy sphere of hermetic knowledge penetrable only by initiates; as my colleague Bob Archambeau (who provides excellent coverage of the day I missed over at his blog) remarked this afternoon, the major difference is that abstractions like difference assume the role that myth reserves for the gods. And there are generational differences; in his conversation with Mackey, Joseph Donahue remarked that in Michael Palmer's work there's a layer of irony calling attention to the gap between the world of myth and the disclosure of reality that myth promises, whereas Duncan's writing is an irony-free zone. (This also explains my preference, when the chips are down, for Jack Spicer, and my sense that ours is a fundamentally Spicerian moment.)

Post-structuralism is the received mythic structure of poets younger than Palmer, many of whom are disturbingly uncritical about it; at least, that's how I'd describe the post-Language crowd. Frank O'Hara, on the other hand, freely mythologized his own life, offering a charismatic model for poetry's relation to myth that has similarly become encased in irony for the nth-generation of New York School practitioners (a practice that goes hand in hand with the ironic mythification of pop culture—though you can't ironize capital, and references to Hanna-Barbera cartoons from the 1980s can be just as effective and exlusionary in establishing one's cultural bona fides as Pound's use of Greek and Chinese characters).

The poets who still engage with myth qua myth are harder to assimilate into groups, which is one of their strengths: here I think of Olson-indebted poets like C.S. Giscombe and Dan Bouchard, and Duncan-inflected poets like some of those prominently featured at the symposium: Mackey of course (whose great contribution comes in reimagining and restructuring the Modernist appropriation of African myth) and also Peter O'Leary. If I had to choose a mode, I'd say Olson's archeology of morning is a more attractive model for the process of assimilating myth into poetry than Duncan's hermeticism. But there's no question in my mind that Duncan wrote better poetry.

There's no getting away from myth, then, or no evasion of allegory, to shift to the term that the conceptual writers have sent buzzing into my head for the past several months. One is always working with some felt (if often untheorized) structure of knowledge and feeling that poetic language rises from and intersects, like a net taking shape around something unseen in deep water; a thing that in its hiddenness, its occultness, is at least homeomorphic with the Real ("a primary reality in itself, having volition"). What I ask of a poet is not that he or she explain myth, but that its force be fully felt: if I can't get a theoretical discourse around it (that's what makes me most comfortable, but who wants to be comfortable?) then I want to feel, for lack of a better word, the myth's authenticity for that poet. Or as I tell my writing students, Don't write about any gods you don't actually believe in.

What follows are some less organized thoughts based on the notes I took during the reading and subsequent panel discussion:

John Tipton introduces Palmer, telling us, "A Michael Palmer poem is not received," and quotes a phrase of Gadamer's characteristic of the poetry: "the questionability of what is questioned." (I hear in this an echo of Duncan's definition of "responsibility" as "Maintaining the ability to respond.") Talks about how, like a famous photographer of industrial sites whose name I didn't catch, Palmer can arrange banal images in a way that we can "hear" and so make us think about them. Speaks of Palmer's next book, to be titled Thread.

Michael takes the stage in brown shirt and brown suit. Begins with some poems that incorporate subtle bits of rhyme, which I love. English rhyme can help retrieve his poetry from the sense it sometimes gives of having been translated from the French. Reads a poem with a personage named "the Master of Rochester." Ashbery? This intuition seems confirmed by a prose poem, "L'Agir," that addresses Ashbery directly.

Hearing Stevens in the surprising words "dudes" and "squeezebox."

A gorgeous poem "After Hölderlin."

"Madman with Broom." Drily: "A poem about the Bush years. You remember them. Great times, they're gone." The central image is of a man trying to drive away crows with a broom – "realist crows," Palmer says, a phrase from Stevens' dreadfully titled poem "Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery."

Here's "Poem against War" in its entirety: "She raises both arms / to free the clasps binding her hair"

Funny poem called "Traumgedicht" featuring a dream of Gustav Mahler in a café listening to… Gustav Mahler. Nudging the speaker: "It's so much deeper than Strauss, don't you think?" I never really noticed this preoccupation of Palmer's with masters and mastery before. Of course he himself is a master.

"lodestar, lexicon, labyrinthos"

"It is the role of the lovers to set fire to the book."

Does Palmer put air quotes around mythic images as well as banal ones? The word "pentacles."

Now Mackey, Donahue, and O'Leary take their seats. Mackey is advertised as a man who speaks in complete paragraphs. A phrase from Olson, via Mackey: "I care for a field of discourse: call me tantra."

They discuss the "high style" in poetry and how Duncan sought to reclaim it. William Carlos Williams, who did so much to speak up for the American vernacular and against the "catastrophe" of appropriating European discourses and structures, nevertheless resorts to the high style more often than you'd suspect. And Duncan, as Mackey says, sometimes recognized a need to come down from his "high hypnagogic mode."

(High style. Masters. Is it a will toward monoglossia? Is that where myth becomes capital, a form of power and domination? I think of The Education of Henry Adams and "The Virgin and the Dynamo," which I taught as the last text in my nineteenth-century American literature class. About how Adams claims that the mythic figures of the Virgin and Venus have no force for Americans, but evoke at best only an empty sentiment. A feeling to be consumed, not a force for production (thinking of his claim elsewhere that the Virgin essentially caused Chartres Cathedral to be built). By contrast the dynamo, modern technology: but Adams sense of its "moral force" is surely anachronistic, all the more so now that we don't even have mythic machines, like the dynamo or the steam engine, to confront as emblems of our own alienated majesty. As Adams says, the world of the new science is "supersensual"—not supernatural.)

Instead of narrative in poetry, the world-poem, world-making. "A better word for story as far as Duncan goes would be fate." (Does myth-based poetry engage directly in world-making, sidestepping or subsuming narrative? Foregrounding the machinery of meaning-making, turning allegory into atmosphere, that which pervades and rises, supersensually, from the ground of language?) Mackey: "Paradoxically, the world-poem is a broken poem. That guarantees its truth." "Incident" as a link to story but not itself a narrative.

Mackey on serial form, as practiced by himself and Duncan: it's a form of apocalypse, an ongoing revelation and uncovering, always incomplete.

Mackey: Poetry as "prophylactic," that which makes it possible to encounter and handle terrifying truths. Which connects obscurely back to a connection Donahue tried to make earlier between the high style and "ecstasy.

(Poem as armor? Can only be justified by the worthiness and power of one's opponent. A knight in shining armor is ridiculous and out of place with no dragons in the vicinity.)

Mackey bringing African myth into the field of American poetry, Modernist poetry. (It seems that an ethnopoetic myth has more urgent reason for being, given the leveling tendencies of a white-operated culture industry.)

(If myth is played with, as Mackey seems to be suggesting—played the way a jazzman plays his horn, in the spirit of improvisation and collaboration—that might be a way round the problem I formulated earlier: myth as capital. That is, the gift economy, or potlatch. Creative destruction.)

(But myth is always collapsing into kitsch. Which at least removes the mask. Camp and kitsch may be the best means we have of encountering capital in the cultural field and discovering/declaring that the emperor has no clothes.)

[UPDATED 5/3/10]

Monday, April 26, 2010

Late Adopter

Yes, you can now follow me on Twitter @joshcorey. This is an experiment that I mean to try for a few weeks and then I'll assess whether it serves a purpose that complements this blog and its own obscure purposes. As I'm no doubt not the first to observe, the 140-character limit is a tantalizing sort of constraint, ideal for producing tweets that operate for all intents and purposes like lines of poetry. And yet the "turns" between lines are collaborative: the sidebar at right deceives in presenting only my tweets. What seems more native to the experience of Twittering is absorbing whatever I might have to say as one among a cacophony of voices that the consumer, not the producer, controls.

So far on my own feed I mostly have institutions—NPR, the Times, the Poetry Foundation—as well as a few easy-to-find prominent individuals like Susan Orlean. (So far I've resisted Ashton Kutcher.) But my own Twittering will probably not come into its own until I'm "following" a suitably eclectic mix of other Twitterers, some of whom will no doubt be engaged in their own quasi-poetic and quasi-critical experiments.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

From Denver

Wednesday:

- Arrived today, made very welcome. The air is thin and the light is hard.

- Immediately run into Mark Tursi and Johannes Göransson at the hotel. Beers around the corner at Leela's. Topics include: small-press publishing, reading fees, Jennifer Moxley is our Tennyson, Mark Levine's poetry, guilty pleasures, Romanticism, flarf.

- Go up to hotel room. Come back down from hotel room.

- Thai noodles with Richard Greenfield and, briefly, Carmen Gimenez Smith.

- The Omnidawn/Ahsahta reading at the Magnolia Ballroom. Open bar for first hour. Sit with Richard, Dan Stolar, Dan Beachy-Quick. Seemingly dozens of readers in quasi-alphabetical order; last only to the end of G. Richard has become a very strong and confident reader. Sneak out after his reading with Sarah Gridley.

- Second dinner at overpriced Italian place with Sarah Gridley. Topics: overpriced wine, rush matting, family, dissatisfaction with poetry, old friends.

- Midnight double scotch with Christian Bök, Jon Paul Fiorentino, and assorted Canadian comrades. Topics: Christian's "Xenotext Experiment," my "Poem for the Inaugural Poem," Jon's "Stripmalling," favorite Canadian versus American cities, the United States as greatest/worst country in the world.

Thursday:

- Breakfast with my chair and colleague Davis Schneiderman. Topics: our respective paths to academia, Ithaca, NY, William S. Burroughs, the challenges of getting enough protein when you're a vegetarian. (I had bacon.)

- A little late to 9 AM panel on integrating wireless technology and social networking into the poetry classroom. Read all about it: http://networkedpoetry.wordpress.com. I most like Eric Baus' idea about exposing students to poems through audio recordings, preferably multiple versions, before they read the poem, as a way to break away from poem-as-inviolable monument.

- Assorted characters at bookfair, too numerous to list here. Buying very little as yet. Susan Schultz gifts me with a desk copy of Hazel Smith's The Erotics of Geography when I remark that I might want to use it in my senior seminar next year alongside The Writing Experiment. Shanna Compton sells me a copy of Bloof's latest, Peter Davis' Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! which made me laugh out loud. They're prose poems that are kind of like the voice-overs to other poems. Here's one in its entirety:

Poem Addressing My Past, Current and Future Students Who Are Sufficiently Interested in Our Class to Check Out My Work

I hope you learn something from this poem and the powerful, mystical way it concludes!

- Noon panel, "Women & Nature, Thirty Years Later: Our Evolving Otherness." Stay only long enough to hear Sarah Gridley's lyrical essay on Simone de Beauvoir and Medusa. Dodge out to other noon panel, "Poetry and Memorability." Stay only long enough to hear Paul Hoover conclude a talk on the poetry of memorability (beginning, middle, end) and the poetry of forgetting (middle, middle, middle). How even the latter—Language poetry for instance—has trouble not producing metrical, memorable lines. Am reminded of this when I return to the bookfair and encounter Johannes again along with Kasey Mohammad, where the conversation somehow turns to the David Lynch version of Dune, and I realize that free verse, et al, is simply an ingenious way of preventing sandworm attacks. To break the pentameter, that was the first heave of Muad D'ib.

- Attend bizarre smackdown between Tony Hoagland, egotistical humanist, and Donald Revell, ascetic desert father, at panel with the misleading title "Poetry After the '00s: What Comes Next?" It was supposed to include Stephen Burt and Laura Kaischiscke, but instead turns into debate between two poets who seem mostly unqualified to talk about "next." Hoagland is pluralistic in a sneakily dismissive way, acknowledging the tremendous energy of contemporary poetry but coming down hard on the side of poems with tones that communicate "existential weight." He thinks the purpose of poetry is to bring the reader to presence. Revell comes across as a Christian Buddhist; for him the "new poetry" can't exist yet or we can't recognize it because it's going to take us beyond the human to "the other shore." Could be talking about nirvana, is really talking about Jesus. There are a few worthwhile aphorisms (Revell) and bits of repartee (Hoagland):

- Revell: "As long as we don't say anything, Tony and I always agree." Hoagland: "That's so postmodern!"

- Revell: "Humanity is one of those experiments that didn't quite work out." "What is humanity except a genre?"

- Revell : "Most poems are rearranging the furniture in the Norton Anthology." "What is a line? it's a turn. It's a conversion. If you are not willing to be converted, you are not able to write line two of your poem." "'I remember poetry! It sounded like this!' Which is what most poems are…merely the memory of poems." Hoagland: "Poetry isn't born from the history of poetry. Poetry is born from our suffering."

- Revell: "Anthologies are a form of suffering." "No Christian believes in tragedy. You cannot have a tragic world-view and faith. It all has a happy ending." Hoagland: "I'm looking for a happy middle."

- Revell: "We are so attached to the conversation, so attached to the canon, so attached to the métier, when simply we are called to let go. I happen to believe there is another shore…. We're not going to get there by clinging to the old conversations. Suffering is for schmucks! Stop it! Stop suffering, please! I have to read it!" Hoagland: "There's a bin here for crutches and eyeglasses!"

- Revell: "As long as we don't say anything, Tony and I always agree." Hoagland: "That's so postmodern!"

It's all quite strange. Revell comes across as a "posthuman" (he even uses the word) and could be interpreted as saying, "All poetry is flarf." He quotes Endgame: HAMM: We do what we can. CLOV: We shouldn't. His position is indisputably the more rigorous and ethical one. But he's a Christian, so I don't quite trust that he's credible when he says that we don't know what the new is. It's not the void he's pitching for—he wants to empty poetry out so that his Emersonian faith can come rushing into fill the vacuum. Hoagland's position is therefore the more "human" one: given a choice between nothingness and something, he'll choose something every time. It's bathos. Both these guys are asking poetry to disappear in some sense, to reveal either something or nothing—other than poetry. Why can't it just be poetry? "Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is."

More Thursday:

- Acquire a few books at the book fair, but mostly keep my powder dry. Finally meet Jeffrey Levine and Jim Schley, my new publisher and editor respectively, at the Tupelo Press table.

- Attend Tupelo Press Tenth Anniversary party and reading, shake lots of hands. Read some poems. Fill up on hors d'oeurves. Resume a chat with Tess Taylor that we first began at a Poetry Society of America shindig in New York in 2003.

- Wind up evening at hotel bar where I run into David Lau and Kasey Mohammad. Topics: conceptual poetry, Notes on Conceptualisms (insufficiently rigorous or enabling fiction?), Lana Turner. Early to bed at 11:30.

Friday:

- Foggy, hazy mind in diamond-blue Denver sky. Coffee helps. Attend panel on queer translation with Brian Teare, making a fool of myself beforehand mistaking Nathalie Stephens for Gabrielle Calvocoressi. Stephens and Timothy Liu are the panelists and John Keene is the moderator; Jen Hofer doesn't show. Fascinating and labyrinthine discussions of translation as a kind of metaphor for desire—what's "lost in translation" can be equated with Lacan's La relation sexuelle n'existe pas. That is, one desires to cross the gap between languages but it's what gets lost in that gap that endlessly regenerates that desire. I meditate on the value of queer sexuality as a mode of consciousness that plays with the manufactories of desire rather than simply accepting their products unquestioningly off the assembly line. What would a queer heterosexuality look like?

- Hang out at book fair. Chats with G.C. Waldrep, Paul Foster Johnson, Janet Holmes, Rachel Loden (who generously insists on giving me a much-coveted copy of Dick of the Dead gratis). Sit at Apostrophe Books table and pretend to be a publisher for a while. Run into my old student Emily Capettini, now in the creative PhD program at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

- Attend insufficiently memorable panels.

- Awful dinner at Johnny Rockets. It's all Richard Greenfield's fault.

- Attend WILLA reading at Denver Press Club. It's a worthy organization and the set-up is promising: burlesque dancers, roller-derby girls working security, and feminist poetry. But the place is overcrowded and hot and stuffy and most of the first poems are just plain bad. Escape at intermission, regret not hearing Lara Glenum, Cathy Park Hong, Carmen Gimenez Smith, a few others.

- Encounter Zach Schomburg and Noah Eli Gordon tearing up the open mike at the Mercury Café. Can't tell if they're being ironic or not.

- Maybe it was tonight I had that conversation with David and Kasey?

Saturday:

- Somehow up in time for the Flarf vs. Conceptualism showdown panel, by far the most entertaining official event that I attend at this year's AWP.

- Kasey's intro: flarf and conceptual poetry are the poetry we deserve. Rattles off the numerous critiques of both movements. Claims that they are working to "recycle" the innovations of the historical avant-garde, "because the first times, they didn't take. The opposite of damage control—they try to do the damage that didn't get done before." But it's hard not to get absorbed by the poetry-industrial complex—"It's like fighting the Blob—you plunge in your fist and soon you're just part of it. After all, here we are." Flarf is controversial because it asserts centrality. Conceputualism is suspect because it approaches "relevance." Quotes Unforgiven: "We get what we get. Deserve's got nothing to do with it."

- Vanessa Place's paper is killer: "Notes on Why Conceptualism Is Better Than Flarf." A few gems:

- "Flarf is a court jester. As such, it is still a member of the court."

- "Flarf is a one-trick pony that thinks a unicorn is another kind of horse."

- "Flarf still loves poetry. Conceptualism loves poetry enough to put it out of its misery."

- "Flarf wants to be funny." "Conceptualism wants."

- Flarf engages the amygdale, conceptualism the cortex.

- "Flarf is a whoopee cushion in the world of the new and old lyric poetry. Conceptualism is a fart."

- "Ron Silliman likes flarf. Ron Silliman does not like conceptualism."

- "Flarf looks like poetry." "Poetry looks like conceptualism."

- "Flarf is a court jester. As such, it is still a member of the court."

- Mel Nichols next. "Cute Gone Wrong," referencing Sianne Ngai's "Cuteness of the Avant-Garde." A book called Journey to the End of Taste, about disliking Celine Dion. "Flarf rocks harder than conceptual writing." Kind of a parody of a paper presentation—she talks about what she's going to talk about instead of actually talking.

- Cute = helpless. Perceptions of vulnerability contribute to perceptions of cuteness. Big eyes, floppy limbs, small voice, wobbly head, etc. Extreme youth, harmlessness, helplessness, need. We are hardwired for cuteness.

- Cuteness as what flarf messes with, confusing our aesthetic response. Rob Fitterman: "Don't make it new. Just make it fucked up." The combination of the cute and the horrible.

- Rod Smith poem "Widdle Biddy Bong Story" – baby talk to a parakeet that parodies "I Know a Man."

- Cute = helpless. Perceptions of vulnerability contribute to perceptions of cuteness. Big eyes, floppy limbs, small voice, wobbly head, etc. Extreme youth, harmlessness, helplessness, need. We are hardwired for cuteness.

- Matthew Timmons' presentation is an inimitable and unrepresentable performance. I like this phrase: "The new friction surface modifier." Compares Flarf to Renaissance Faires. "Conceptual writing has been defined by Kenneth Goldsmith as, 'Writing.'" It's all tap-dancing on the edge of the abyss, I think.

- Katie Degentesh talks about vampires versus werewolves: which has more control over its dark side? "Hooking up with a vampire is fun, disgusting, and vulgar." John Ashbery, Kevin Davies, the young Auden, rumored to be vampires."One of the purposes of vampirism is to defeat and render irrelevant close reading." "Shifters hate vampire and vampires hate shifters." So flarf as vampirism and conceptualism as lycanthropy? Or is it the other way round?

- Christian is last. Talks about Kenneth Goldmsith and his essay that argues that flarf is Dionysian and conceptualism is Apollonian. "Being somewhat lazy, I have decided simply to read you that essay by Kenneth Goldsmith…but using the techniques of flarf, albeit in a more advanced and rigorous manner." Paper title: "Flarf! Arf Arf Arf!" Another inimitable performance but:

- "We imagine that a bottle of cleaning fluid must be totally fucking clean inside!"

- "I steal the letter M because it seems like the letter M must weigh the most."

- "I write a few sincere lines, and then I have to make fun of them."

- "We imagine that a bottle of cleaning fluid must be totally fucking clean inside!"

- Kasey's intro: flarf and conceptual poetry are the poetry we deserve. Rattles off the numerous critiques of both movements. Claims that they are working to "recycle" the innovations of the historical avant-garde, "because the first times, they didn't take. The opposite of damage control—they try to do the damage that didn't get done before." But it's hard not to get absorbed by the poetry-industrial complex—"It's like fighting the Blob—you plunge in your fist and soon you're just part of it. After all, here we are." Flarf is controversial because it asserts centrality. Conceputualism is suspect because it approaches "relevance." Quotes Unforgiven: "We get what we get. Deserve's got nothing to do with it."

Q&A. Aaron Kunin questions Vanessa as to what she means by allegory. Allegory = reference to extra-textual narrative. Radical evil: a poetics that is an affirmative will to evil toward poetics itself. Another Q for Vanessa: conceptualism addresses a fundamental absence. Using Lacan. Absence of meaning/signification, desire for same. There's something that's not there: ideally the person who reads the text enters that space and puts its (?) desire into the work. The thing in the poem is not what satisfies—radical evil asks, "How can I take that thing away from you?"

Good stuff.

- Books, books, books. I can't write down all the titles because I haven't unpacked my suitcase. Especially pleased, though, to have acquired John Beer's miraculously titled The Waste Land and Other Poems (aren't you jealous you didn't think of it first?) from the Canarium table; a sheaf of essay chapbooks from Ugly Duckling Presse; a pile of beautiful Wesleyan hardcovers, deeply discounted, by Brenda Hillman and Roberto Tejada and Rae Armantrout and Kazim Ali.

- Lunch with Sarah Gridley, then we hike over to the Museum of Contemporary Art for the flarf/conceptualism reading—it's not Sarah's thing at all, but she's curious. The reading is less satisfying than the panel—it comes off as something of a refuge for smug hipsters, though Christian's sound poetry is always delightful and it was amazing to hear Christine Wertheim, whom I think of as a visual poet, do uncanny, jouissance-inducing moves with her voice. Argue about its relevance and value with Sarah all the way back to the hotel instead of attending the rooftop party for flarftinis.

- A well-deserved nap.

- Cab it out to the Plus Gallery for the Possess Nothing mega-reading organized by Richard and Mark. The stand-out readers are Johannes (reading from A New Quarantine Will Take My Place), Gordon Massman (talk about queer heterosexuality! reading from The Essential Numbers 1991 – 2008), and Abraham Smith, an electric hopping presence (reading from a book I regret not purchasing, whim man mammon). Afterward fall in with Johannes who insists on "famous tequila shots" and leads a small group of us, pied-piper style, to the Whiskey Bar. I wander off and meet Mark and Richard for late night fish n' chips at a pub.

- Home to bed at the semi-reasonable hour of 12:30. Up today at 6 for the flight home.

Popular Posts

-

This is gonna be a loooooong post. What follows is a freely edited transcription of my notes from the Zukofsky/100 conference at Columbia t...

-

Will be blogging more or less permanently now at http://www.joshua-corey.com/blog/ . Or follow me on Twitter: @joshcorey

-

Midway through my life's journey comes a long moment of reflection and redefinition regarding poetics (this comes in place of the conver...

-

My title is taken from the comments stream of an article recently published by The Chronicle of Higher Education , David Alpaugh's ...

-

Elif Batuman has amplified her criticism of the discipline of creative writing (which I've written about before ) in a review-essay that...

-

Thursday, September 29, 2011 Berlin. Fog of sleep deprivation coloring an otherwise perfect blue autumn day a sort of miasmic yellow i...

-

Trained it down to DePaul's Loop campus this morning to take part in a panel, "Why Writers Should Blog," alongside Tony Trigil...

-

In one week Lake Forest will hold its commencement and I'll take off my professor's hat for the summer. A few weeks later, in June, ...

-

Farewell, Barbara Guest .

-

That's one of my own lines. From an untitled (they're all untitled) severance song: After form fails a furling, reports dying away, ...