In Rome I found the young man in whose honor

We sacrifice at our altars every month.

He said, "Go feed your flocks as in the old days;

Herdsmen, raise your cattle as you used to."

(David Ferry, trans.)The uncanny quality in this eclogue is the absence of jealousy or political friction between the dispossessed Meliboeus and that fortunate senex Tityrus; "It's not that I'm envious, but full of wonder." The dialogue becomes Meliboeus' elegy for the life with flocks and fields that he will know no more, and ends with Tityrus' invitation to linger for at least one more night as his guest, for, "Already there's smoke you can see from the neighbor's chimneys / And the shadows of the hills are lengthening as they fall. " Et in Arcadia ego: not just physical death, but social and economic death, are part and parcel of the pastoral experience, and Tityrus has no guarantee that "the young man" in Rome won't change his mind tomorrow about his status.

This possibility is elaborated in the ninth eclogue, which essentially retells the story of the first from the dispossessed shepherd's point of view. "A stranger came / To take possession of our farm, and said: / 'I own this place; you have to leave this place.'" To which his interlocutor, the naive Lycidas (whose name Milton will take for his great pastoral elegy of that title) responds:

But I was told Menalcas with his songs

Had saved the land, from where those hills arise

To where they slope down gently to the water,

Near those old beech trees, with their broken tops.

"Yes, that was the story," Moeris replies, "but what can music do / Against the weapons of soldiers?" And once again elegy, that nearest neighbor to pastoral (and isn't "pastoral elegy" very nearly a synonym for "necropastoral"?) takes hold as the two shepherds sing sorrowfully of a land that seems always already lost: "Time takes all we have away from us." The master poet, Menalcas, who was powerless against political violence, remains offstage in this eclogue, like Godot; "The time for singing will be when Menalcas comes" is the poem's last line.

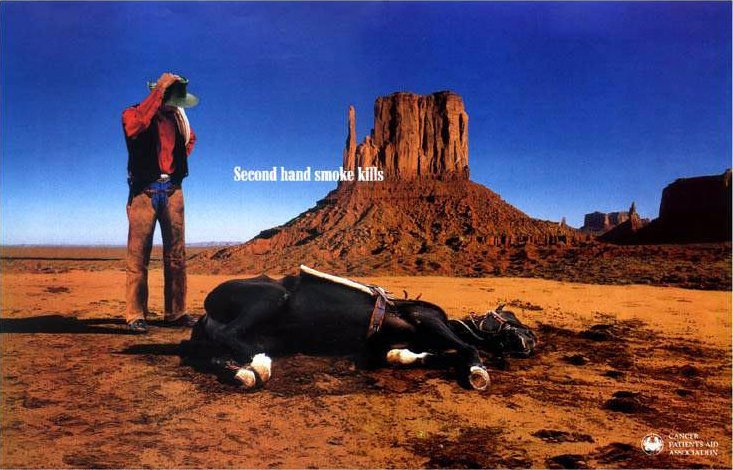

It's impossible to read these poems and feel assured of pastoral as the perfect fantasy of the locus ameonus or virga intacta that it presents itself as in its most ideological forms (the Marlboro Man, for instance, though of course even his iconography has become infected by death). Consider, too, Leo Marx's characterization of American pastoral in particular as the conjuration of a "middle landscape," ideally situated between a hostile wilderness and the corruptions of capitalism. But his book The Machine in the Garden is a close examination of how the boundary between the two is actually a wavery and porous line. Its iconic scene is an excerpt from Nathaniel Hawthorne's notebook, in which a forest revery is interrupted, then reconstituted, by the sound of a locomotive thundering not so very far away.

In Deleuzeian terms, a pastoral poem deterritorializes or rhizomes (if that can be a verb) the landscape it reflects, but the most interesting such poems don't close the loop through an authoritative reterritorialization. Instead the represented landscape remains open, infected if you like, by the visible passage of the reader's desire to flee complexity/multiplicity/the city/death. McSweeney's necropastoral, in my view, is valuable insofar as it's an updating of the pastoral to be responsive to the most current environmental conditions (taking late capitalism in this sense as the environment or "climate" of contemporary poetry). I'm especially interested in her notion of necropastoral as a means of processing (or maybe "confronting" is a better word) "contamination," both in its ideological senses (the racist pastoral fantasy of the anti-immigration America First crowd) and its biochemical one. As Joyelle puts it, "the necropastoral is the toxic double of our eviscerating, flammable contemporary world, where avian flu, swine flu, mad cow disease, toxic contamination via industrial waste, hormones in milk, poisons leaching out of formaldehyde FEMA trailers, have destroyed the idea of the bordered or bounded body and marked the porousness of the human body as its most characteristic quality."

I wonder if Joyelle has read any Bruno Latour, who has introduced the concept of the "quasi-object" to ecological thought: a social "object" which is also kinda-sorta a subject, of which toxic entities like hormones in milk are pardigmatic examples. This would be the darkest example yet of necropastoral, in that it parodically achieves the reconciliation between subject and object, self and other, human and nature, that is at the root of the pastoral fantasy. The (contaminated) body becomes indistinguishable from its (contaminated) environment. It's difficult to be sanguine about this from the perspective of normative environmentalism, but it's exciting allegorically, as a means of imaginatively contesting fundamentally undemocratic fantasies of purity (something ecology at its most misanthropic is fully capable of manifesting).